|

Cholera: Fever, Fear and Facts A Pandemic in Irish Urban History |

|

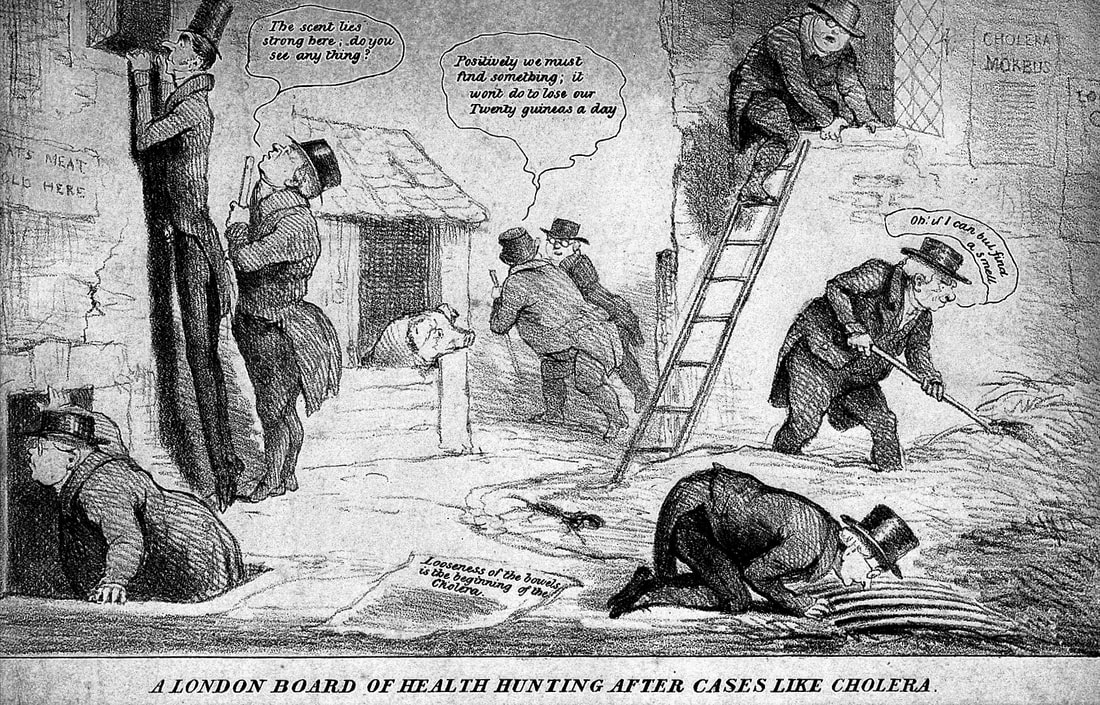

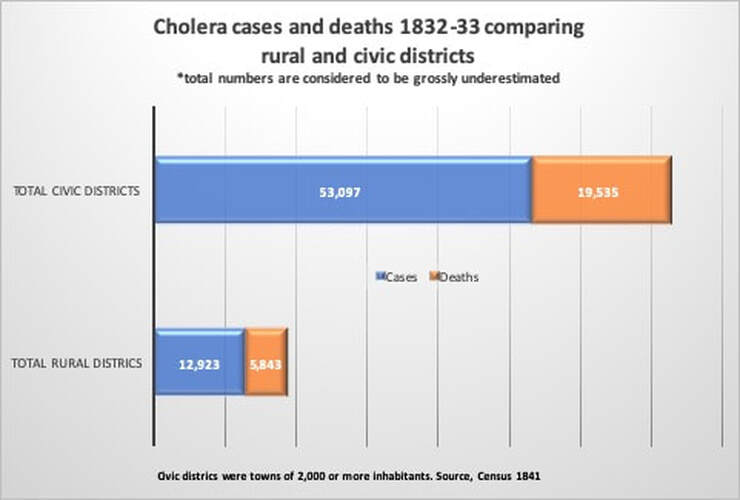

Social distancing - a new reality that most of us are finding difficult: being physically separated from our families and friends, and unable to express affection, support and solidarity with our fellow humans. We are, after all, social animals, hardwired for proximity to each other. The idea of isolating people in times of sickness, is however, as old as society itself. In the past 'maintaining your distance' was an important part of public life, particularly between social classes and genders. Historically, public health actions have done more to stem disease than modern medical or pharmacological interventions. Throughout Europe during the Great Cholera pandemic of 1832, desperate coercive measures to prevent the spread of the disease were enacted. In Russia troops surrounded infected communities with orders to shoot those who tried to leave. In Spain it was punishable by death to leave an infected town. British authorities, mindful of international trade, hesitated, (then, as now), eventually implementing less coercive measures to contain the pestilence. Initially, the government imposed local quarantine measures at British and Irish ports, but there was significant opposition from commercial interests who did not want goods delayed; additionally, the unpredictable geographical spread of cholera outbreaks made port restrictions seem inadequate. Quarantining of the sick was a standard practice by 1832, and often prevented larger-scale infection; however, a number of political, social and economic circumstances in the Ireland of the day, mitigated against any large-scale imposition of quarantine. The Irish Central Board of Health faced a dilemma. If they employed a strict quarantine on travel to towns and ports, there would be clear economic repercussions. Extensive social unrest was a real possibility, given that the often-violent campaign against the Tithes, or taxes on land, was at its height. Large gatherings of protesters in provincial areas continued throughout the epidemic, and this must surely have enabled the spread of the disease. Many preventative measures used against the spread of Cholera, strike a chord with us today during the Coronavirus pandemic. Sick victims were to be reported to the medical officer, and then removed to a hospital. Mass gatherings and funerals were banned, as authorities felt the custom of the ‘poorer classes’ to visit their sick neighbours, and attending the wake-house, would contribute to the spread of the disease. In Cork a priest was assaulted when he opposed mourners attending a wake-house. Ordinary burial rituals were abandoned, as the sheer number of dead overwhelmed churchyards and many ‘Cholera Trenches’ were opened for rapid disposal of infectious corpses. Markets and fairs were banned as the death rate soared, shops shut down, and the streets of Irish towns emptied. Enforced incarceration, and a deep mistrust of medical doctors amongst the poor, meant that any attempt at quarantine was badly received. In Tipperary town, a mob prevented a patient being removed to the hospital by medical officers. In Bundoran, the seaside visitors fled the town, with roads blocked by carriages and foot passengers, ‘all escaping from the scenes of death’. Tullamore was similarly abandoned, ‘crowds armed with pitchforks, congregated on the roads threatening anyone going to or coming from the town’. A portion of the Grand Canal was drained to block canal traffic. Ireland’s huge number of highly-visible beggars - typically women and children - were suspected of carrying the cholera from town to town. These mendicants, very mobile, were prevented from travelling, and those native to a town were ‘badged’, or registered, so that they could be clearly identified as distinct from ‘other beggars and mendicants’, who may have been harbouring cholera. Urban RefugeesBoards of Health were encouraged to set up temporary hospitals, but most were vehemently opposed. Ballyshannon mobs threatened the local landlord who dared to provide a building for a hospital. In several Irish towns, field hospitals were set up, utilising old storehouses, and even erecting tents near existing Fever Hospitals in order to cope with the swelling numbers of diseased victims. Normal town and village life in Ireland came to an end, as communities and individuals tried to isolate themselves for fear of catching the disease by physical contact. Sligo, a prosperous town of 15,000 people, was abandoned as the cholera struck. Only an estimated 4,000 people remained, with the rest escaping into the adjacent countryside, camping under hedges and in ditches, where makeshift shelters dotted the landscape. The wealthiest families paid up to £50 for accommodation in a small room in the countryside. So great was the fear of contagion amongst local country people, that few would give shelter or food to these ‘urban refugees’. A ‘cordon sanitaire’ was set up around the town, in order to prevent people from leaving. Provisions on the way to Sligo town were stopped, trenches were dug across the highways, carriers from Enniskillen was turned back, and a blockade was set up on the main road to Donegal. Prices for food and provisions increased rapidly due to lack of supply. The daily Mail Coach from Dublin appears to have got through, possibly due to its armed guards. Sligo was noted in contemporary reports as ‘strangely silent’ during the epidemic. There was complete suspension of business and an entire absence of people from the streets. ‘The only sounds heard were the footsteps of those running to seek medical aid, or the hurried footfall of the medical men, and the dreaded rumble of a cholera cart conveying the dead to the burial ground’. Commentators noted the absence of birds during the course of the contagion, probably due to the constant fumigation. Self-imposed quarantine appears to have worked in some situations, as not a single case of fever occurred at the Charter school, nor Sligo gaol, which had their own uncontaminated water supply. Sligo town recorded over 1,400 cases of Cholera, with almost 700 deaths. The mortality rate was 47.5 percent; without the flight of its people, the final toll would have been more.  Charlotte Thornley, later to be the mother of Bram Stoker, then a 14-year old girl, lived with her family in Old Market Street in Sligo. She wrote a memoir, about her experiences of the cholera, and the fact that her family survived untouched. The Thornley’s stayed quarantined in their house and fumigated it daily; they may also have had their own well, thus avoiding contaminated water. Their street was one of the few with a new sewer running through it, perhaps protecting them. Many of the Thornley’s neighbours, including a Dr. Little, died one by one, and were carried away. Charlotte has left us with a heart-rendering account of her young neighbour, Mary Sheridan, left dying alone; ‘We could hear her crying! I begged my mother’s leave to help her. She let me go with many tears. Poor Mary died in my arms an hour after and I returned home, and being well fumigated was taken in and escaped’ [the disease]. It is difficult to ascertain if isolation as practiced in Ireland during the cholera pandemic led to a reduction in death rates. What we can say, is that the number of cases and deaths were significantly lower in rural areas than in the unsanitary towns. Exceptions to this trend were in the densely settled countryside of rural west Cork, west Donegal, and west Mayo, where heavily clustered traditional clachan-type settlements, were as prone to the march of cholera as was a Dublin tenement.

5 Comments

Raoul

4/18/2020 06:15:00 am

Great article. With what did they fumigate that prevented cholera spread?

Reply

Fiona

4/18/2020 08:17:13 am

Thanks Raoul, Fumigation with a strong and foul-smeling agent was a traditional reaction to disease. In the streets barrels of tar and pitch were burned, and in buildings. fumigation was attempted by burning sulphur in small iron pots, creating sulphuric acid clouds. Whitewashing with lime, and cleansing with hot lime wash was more scientific - lime has sterilising and antibacterial properties.

Reply

John Quinn

4/18/2020 05:42:39 pm

Hi Fióna,

Reply

Aileen Hanley

4/21/2020 01:59:56 am

Wonderful description as I know little about Sligo history

Reply

8/1/2022 01:06:30 pm

Instagram anlık beğeni satın almak için web sitemizi ziyaret ederek kolay yoldan Instagram beğeni satın al seçeneklerimizden faydalanabilirsiniz. Hemen bağlantıya tıkla ve Instagram anlık beğeni satın al. https://ttmedya.com/instagram-begeni-satin-al

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Dr. Fióna GallagherProfessional Historian. Main area of interest is in urban history, and the social and economic sphere of Irish provincial towns after 1700. ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed