|

Cholera: Fever, Fear and Facts A Pandemic in Irish Urban History |

|

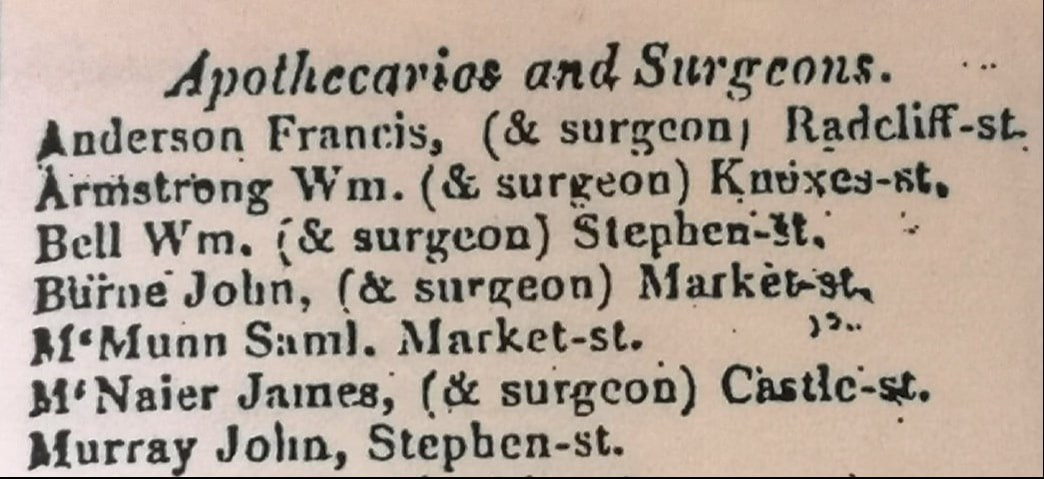

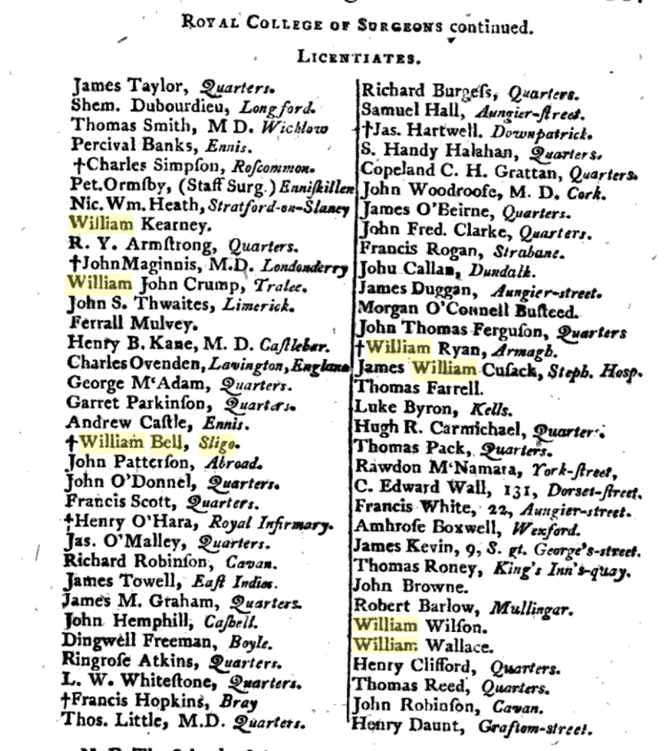

Today, Healthcare Workers are in the frontline of the Coronavirus pandemic, varying from highly-trained specialists to the non-medical ancillaries, providing the backbone for our hospitals. In the past, the delivery of care to the sick was not as sophisticated as now, but medical and logistic experience gained from Irish epidemics over the last 200 years, has been invaluable. In the pre-famine period, physicians, surgeons, apothecaries, midwives and medical officers operated across a wide-array of private practice, charitable & fever hospitals, dispensaries poor-houses, and home visitations. During the 1832 Cholera epidemic, the rudimentary Irish medical system was challenged in several ways, not least in the exposure of doctors, nurses and attendants to the disease. While death-rates amongst the poor were greater, cholera struck down the better-off as well. Among the higher classes, doctors, apothecaries and clergymen were particularly at risk, for their duties brought them into close contact with the sick. A great obstacle to setting up cholera hospitals was the difficulty in hiring staff to look after the infected patients. Nursing was not a recognised profession in the 1830s; a Matron’s role at hospitals was primarily an administrative one. Nursing attendants, or ‘nurse-tenders’, often male as well as female, were confined to washing and feeding patients and cleaning the wards, and were poorly educated and paid. A higher standard of nursing care, came from religious sisters, most notably the new congregations of un-cloistered nuns, who, fulfilling their vows of charity, visited the sick poor in their homes from about 1820. During the Cholera epidemic both the Mercy Sisters and Sisters of Charity served at Grangegorman and Townsend Street in Dublin, for several months, where their strict religious discipline and attention to cleanliness, yielded good outcomes, and was much-commented on by the medical men. The success of their endeavours led to three Sisters leaving for Paris in 1833, for specialist nursing-study. In 1835 Mary Aikenhead founded St Vincent’s, a free hospital wholly-owned and operated by religious women who were also qualified nurses, in a profession then utterly dominated by men. In Dublin, competent lay nurse-tenderers worked in Grangegorman and the mendicity institutes, and several hundred of these served diligently in the capital, even helping to bury the dead. The professionalisation of nursing as a secular job was not to happen until Florence Nightingale's establishment of St. Thomas's in 1860. The practice of medicine however, was a largely a profession for the sons of the gentry and the upper-middle classes; a ‘respectable class of society’. The profession was characterised by a tripartite division of physicians, surgeons and apothecaries, who looked upon each other as ‘practitioners of totally different trades’, rather than colleagues. One thing however, united them all; a high level of mortality. As Geary succinctly puts it, ‘Medicine was a dangerous occupation in pre-Famine Ireland’. An 1843 survey undertaken by renowned doctors Stokes and Cusack, concluded, that ‘in Ireland a medical officer runs a greater risk of death from contagious disease than perhaps any other country in Europe’. Irish doctors were more exposed to diseases than the middle-class was generally, and over a long period of their professional lives. A significant proportion of doctors in the pre-famine period contracted Typhus, then endemic amongst the destitute poor. Medicine was a hierarchy, with clear lines of demarcation. Physicians were considered the senior ‘learned’ profession, recipients of a university education, with an extensive knowledge both medical and philosophical. Surgeons, licentiates of a professional body, (the RCSI), were regarded as skilled craftsmen, served a robust apprenticeship studying anatomy, surgery and pharmacy, but were regarded as ‘professionally inferior’ to physicians. In fact many surgeons of the time in Irish hospitals were battle-hardened, having served in the army during the Peninsular wars, where they acquired remarkable experience which allowed them to administer innovative treatments when they returned home. Licensed Apothecaries, (akin to modern pharmacists), compounded their own medicines, and gave minor medical advice. Many surgeons were also apothecaries. There was a certain tension between the Apothecaries and Physicians over the compounding and sale of medications, and what the Physicians viewed as apothecaries' unlawful ‘practice of medicine’. However, the services of apothecaries were affordable to the poor, and they considered themselves the historic providers of medicine to the people. Overall, there were great discrepancies in the professional characters of Irish doctors during this period, ranging from total dedication, to the total dereliction of duty, the latter prevalent amongst country doctors. One obituary mentions a nurse, Mrs. Margaret Glancy, of the Antrim cholera hospital, who died on 16 September, having caught the disease while attending a fatal case some days previously. Cholera took a huge toll on medical men around the country, as can be seen through the columns of provincial papers. Between May 1832 and April 1833, around 75 medical men are recorded as dying from Cholera. There were probably many more. The highest toll was on Surgeons, perhaps due to their positions in local Fever Hospitals; Thirty died. Twenty-four Physicians and eighteen Apothecaries also lost their lives. Epitomising the tragedy behind the facts, is Surgeon Alexander McKee, of Moneymore, Derry, aged 45, a garrison surgeon and widower, who died in January 1832, ‘after 22 days of great suffering’, contracted from the poor he was attending at the Drapers Dispensary. He left six infant children without a mother, to deplore his irreparable loss’. In Galway, dispensary apothecary Matt Doyle, succumbed to the fever in May, as did Surgeon Richard Jebb Browne, of Newry, aged 58, one of several military surgeons to die. In Carlow, the assistant Surgeon John Foster and his wife died in early June, one of nine cases in the town, including another physician. The young Dr Connell Evans, a country practitioner from Rathkeale, came to help in Barrington’s Hospital, Limerick, but died 24 hours after coming into contact with his patients. Doctor Cox, late of Portarlington, died at Newbridge on 16th June, collapsing and dying in two hours; an apothecary in attendance at Ennis Cholera hospital, Mr. Carr, died of the disorder on 9th June, followed by his wife less than 24 hours later. Dr Charles Keane, newly married, died on 16th August, ‘a victim to his own benevolence and humanity’; he contracted the disease during his attendance at Limerick and Ennis cholera hospitals. His remains were conveyed from Ennis to the family vault at Kilmaley, west of the town, accompanied by a vast congregation of country people, in defiance of the ban on funerals. Sligo Doctors during the EpidemicSligo was to experience a concentrated and tragic loss of its doctors during the Cholera epidemic. Seven doctors died within eight weeks, including some who had been sent to Sligo by the Central Cholera Board to assist local physicians. In 1832 there were about ten doctors practicing in the town, along with a number of apothecaries. Dr Henry Irwin (c.1770-1836), a former army surgeon, was chief physician at Sligo Fever Hospital when the epidemic hit. He left behind a vivid account affair in the town, and the difficulties faced by doctors and the Board of Health. Doctors Leahy, Bernard Coyne and the Fever-Hospital Surgeon William Bell all died of the pestilence. Surgeon Bell, a licentiate of the RCSI, was buried in the Cholera Pit to the rear of Sligo Fever hospital, along with his patients. Dr Leahy was Professor of Physics at the ‘Kings and Queens College, (RCPI), and had been sent to Sligo by the Central Board of Health, so bad was the situation there. Several private practitioners residing in Sligo also died, including Dr Anderson and his daughter; Drs Beatty, Church and Sherlock, while Drs Devitt and Carter were severely afflicted but recovered. Five other resident doctors attached to the hospital, Doctors Knott and Powell, Murray, Carter, and Tucker, fell ill with the cholera, but survived. A medical student, William Christian, died in May 1833, having survived an attack of cholera the previous September, when he was lauded for his ‘unceasing exertions and benevolent care to the poor’. Many of the auxiliary ‘nurse-tenders’ at Sligo Fever Hospital died or fled in fear. Dr. Irwin, noted that the only replacements that could be employed in place of the regular staff, were the ‘most abandoned of both sexes, several of whom, from their drunkenness and inattention, we were obliged almost immediately to dismiss.’

In our current situation, we can be very glad of our modern medical professionals and their services; they draw on a long line of medical tradition in Ireland.

1 Comment

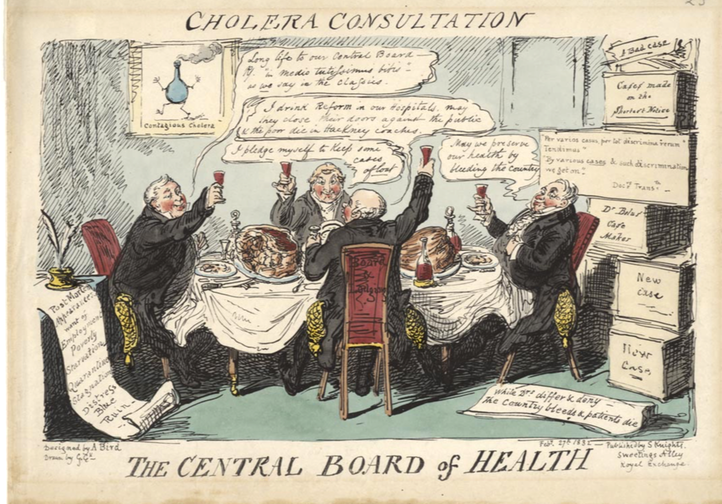

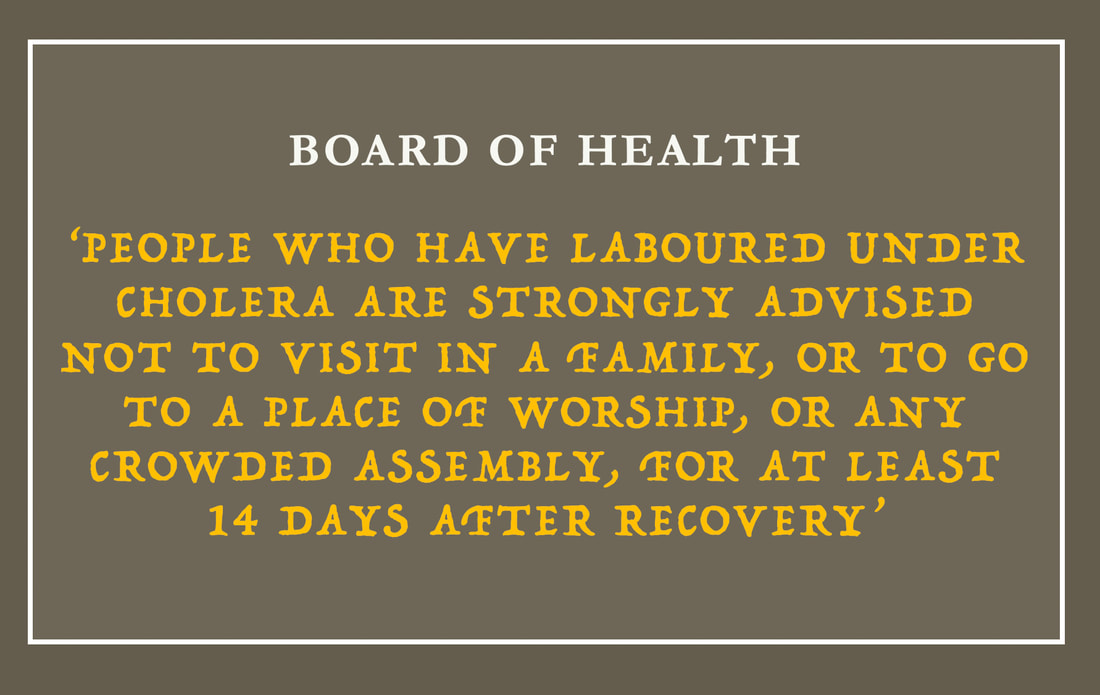

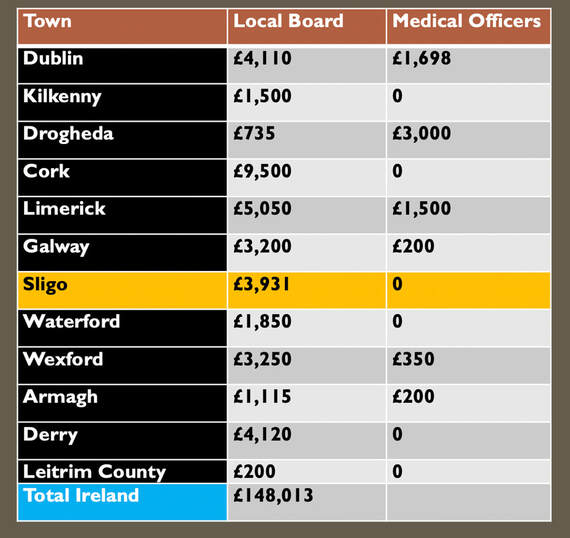

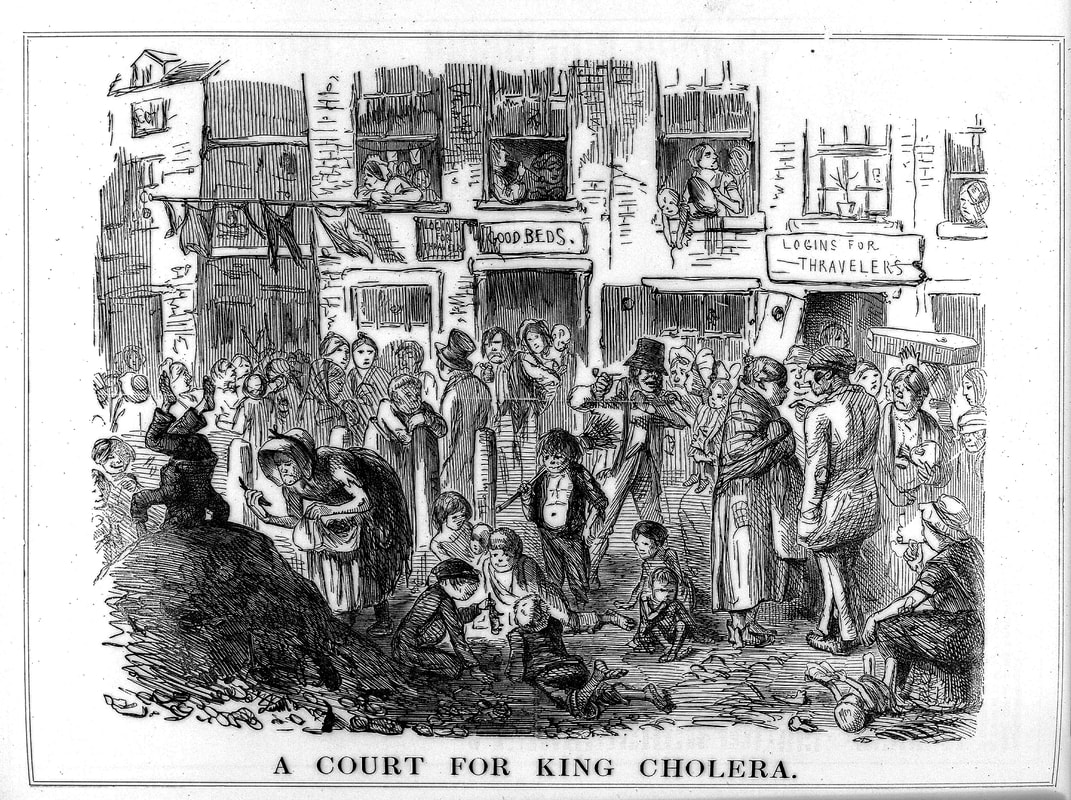

We often look back at history and think that there was no medical care in the past, that people, and more specifically the poor, were left to suffer from the myriad diseases that circulated in pre-Famine Ireland. The dominant political ideology in 18th and early 19th century Ireland and Britain was one of minimalist intervention in medical and social affairs. Disease and poverty were seen as the lot of the poorer classes, their care left to charitable and philanthropic foundations. But by the opening decade of the 19th century, the enlightened ideas of social reformers such as Jeremy Bentham, caused a change in how disease and the poor were treated, not least because of the public threat of infectious outbreaks. Vaccination against smallpox in Ireland began in 1800, and quickly became widespread, and a substantial network of voluntary medical charities were operating infirmaries, mendicity institutions and lying-in hospitals throughout the country by 1832. The Irish Typhus epidemic of 1816-19, in which up to 65,000 may have died, was instrumental in changing the State’s relationship with health and disease, and signalled a more interventionist role from government. County Infirmaries had been established in 1766, under an Act of George III, when an infirmary was established in each county. They were designed to ‘restore the health of His Majesty’s subjects’, and to promote labour and increase productivity. They were financed by a mix of Grand Jury presentments, parliamentary grants, charitable subscriptions and donations. By 1832 there were 31 of these Infirmaries in Ireland, as well as a network of almost 500 free dispensaries for the poor. Fever Hospitals were legislated for in 1818, being erected in areas more ‘susceptible to high incidents of fever’; they were fewer in number, with only six in Connacht by 1832. The Act allowed for the setting up of Local Boards of Health, primarily to deal with local outbreaks of fever and contagious disease. In 1831, as the Cholera pandemic raged, it was realised that it was only a matter of time before it spread to Ireland. Cholera provoked greater fear and thus more intervention, due to the fact that it was a hazard to all classes. In preparation for an epidemic, the government re-activated the Irish Central Board of Health in October 1831. Members were chosen for their background in bureaucratic matters and organisational skills. Regulations and advice were issued similar to their English counterparts, with an emphasis on sanitary precautions. The Board, - often called the ‘Cholera Board’ - used legislation enacted during the typhus epidemic, which it felt was adequate for prevention measures. The Central Board oversaw the Local Boards, and distributed grants. This system was preferred by the government, as much of the costs could be borne locally by raising a poor-rate, and supplemented by voluntary subscriptions. This Board has echoes today, in that its role was to act as a ‘medical watchdog’, collect statistics about local health conditions, and to advise where local committees of health should be set up to combat occasional epidemics. This endeavour marks the beginning of the centralisation of health and medicine in Ireland By January 1832, numerous Local Boards of Health were operational, and were authorized to take all steps necessary to ‘prepare for the onslaught of the disease’. This included the cleaning of the houses and lanes of the poor, burning of unclean bedding, the whitewashing of houses, and the setting up of cholera or auxiliary hospitals. They could borrow funds from the Central Board to finance these measures. The Cholera Board issued a detailed proclamation on 13th April 1832, to be publicly displayed all over Ireland. ‘Everyone affected is to seek medical attention or run the risk of death'. This may seem obvious to us today, but was not necessarily so in a period when mistrust of doctors was running high. In an eerie echo of today’s Coronavirus regulations, the Cholera Board issued robust ‘Notices and Regulations’, and local officers of health were to be appointed to implement these. Existing fever hospitals and county infirmaries were not to be used for infected persons. Suspected cases were to be removed immediately to a temporary cholera hospital, and special accommodation should be set up for that purpose in each town. If no buildings were to be found, improvised premises or tents should be erected. Medical depots were to be established in larger areas, to assure the supply of medicine and equipment. Weekly reports and statistics of the progress of the disease were to be kept, and published in the local newspapers. Those who had suffered from Cholera were ordered to isolate for 14 days after they recovered. The Central Board also sent experienced doctors to places that had severe outbreaks and not enough medical staff. The cost of these men had to be met by the local boards of health. There was a huge emphasis on cleanliness and fumigation, and paradoxically, on the importance of ‘pure water’, along with temperance, and physical exercise. Manure heaps were to be removed, and streets and insanitary lanes swept and washed. Special carriages were constructed to transport the sick or dying to a cholera hospital. Public gatherings were discouraged, (with little success), and wakes and funeral services were halted. Preparations were varied throughout the country. In Kilkenny, there was a ban on the selling of second-hand clothes in the city by March 1832, and a cartload was burned. There was a huge trade in used clothing, imported from England, and there was a justifiable fear that cholera could be harboured in these garments. In Ennis, the local board of health paid 48 men to remove nine cart-loads of manure heaps from the streets. Insanitary privies – dry toilets, - were a particular source of concern, and in Dublin there was the innovative proposal to erect mobile privies, which could be moved and emptied at night. Centuries of exposure to fevers and disease had left the Irish people with a unique knowledge of how contagion and transmission worked, even if they did not understand our modern terms of aetiology and vectors of disease, and preferred to think of infection as originating as a ‘miasma’ or foul air. In Thurles, following the death of a young girl, her clothes were burnt and the house was fumigated by the Board, but a fearful mob burned the house down, inadvertently destroying the house next door. In Drogheda, clean straw for bedding was issued to 2,000 families, and over 540 yards of linen were made into bed ticks, stuffed with straw for the cholera hospital. The Sligo Board received £300 from the central Board in between March and 15th August 1832. The monies advanced were used to finance the cholera hospital, to pay doctors and other medical attendants, and to compensate people for clothes or furniture destroyed. By late August, a further £300 was advanced from the Central Board in recognition of the horrifying state of affairs in the town. A very significant expense was the cost of hiring a ‘large medical staff of porters and nurses’ at the Fever Hospital. Board of Health Grants were subject to repayments at a later date. This had the effect of smaller amounts being granted to poorer parts of the country, as there would be no ‘matching funds’ from voluntary or private subscriptions, raised mainly from the landed classes. While many Irish landlords and monied classes were notable donors, those in Mayo were apparently unmoved by the plight of the sick poor, where fever and distress in 1831 had already left over 200,000 in want of relief.

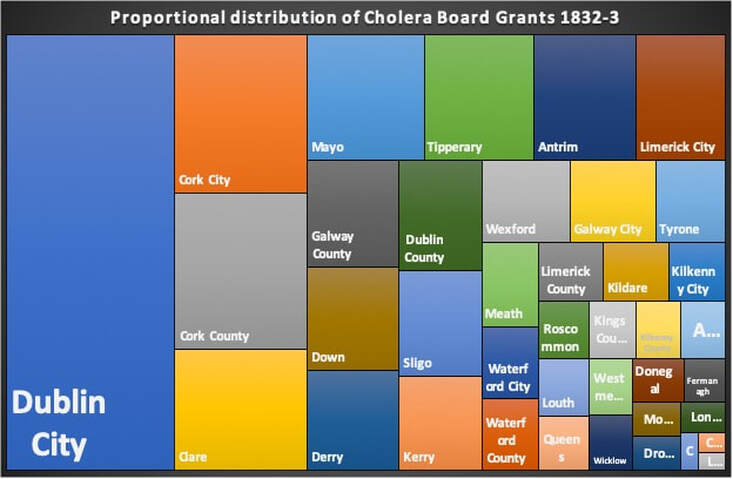

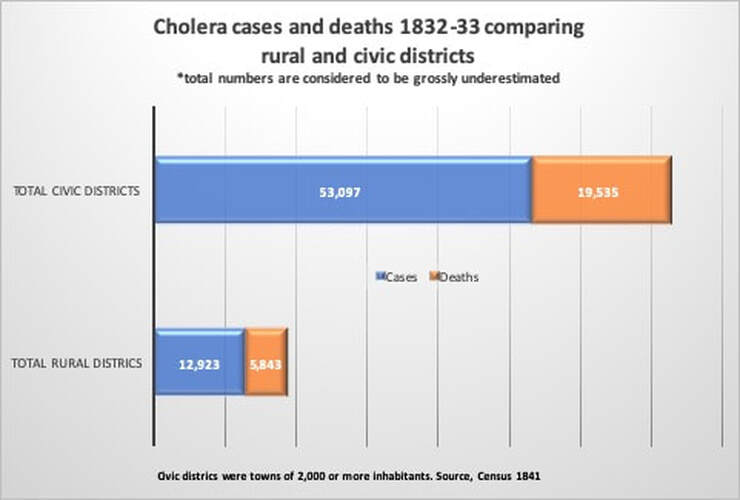

In all, the Central Board of Health made grants to the local boards, totalling £148,103 Sterling, equal to about £14 million today, illustrating that large amounts were spent on combating the pandemic in Ireland, as compared to previous epidemics. Dublin City and County received the most monies, with Cork, Clare, Mayo, Tipperary, Limerick City and Antrim all receiving more than £5,000 in 1832-3. It was still not enough. But given the nature of the disease, and the then confused scientific understanding of cholera’s pathology and epidemiology, further spending would not necessarily have lessened the death toll. Social distancing - a new reality that most of us are finding difficult: being physically separated from our families and friends, and unable to express affection, support and solidarity with our fellow humans. We are, after all, social animals, hardwired for proximity to each other. The idea of isolating people in times of sickness, is however, as old as society itself. In the past 'maintaining your distance' was an important part of public life, particularly between social classes and genders. Historically, public health actions have done more to stem disease than modern medical or pharmacological interventions. Throughout Europe during the Great Cholera pandemic of 1832, desperate coercive measures to prevent the spread of the disease were enacted. In Russia troops surrounded infected communities with orders to shoot those who tried to leave. In Spain it was punishable by death to leave an infected town. British authorities, mindful of international trade, hesitated, (then, as now), eventually implementing less coercive measures to contain the pestilence. Initially, the government imposed local quarantine measures at British and Irish ports, but there was significant opposition from commercial interests who did not want goods delayed; additionally, the unpredictable geographical spread of cholera outbreaks made port restrictions seem inadequate. Quarantining of the sick was a standard practice by 1832, and often prevented larger-scale infection; however, a number of political, social and economic circumstances in the Ireland of the day, mitigated against any large-scale imposition of quarantine. The Irish Central Board of Health faced a dilemma. If they employed a strict quarantine on travel to towns and ports, there would be clear economic repercussions. Extensive social unrest was a real possibility, given that the often-violent campaign against the Tithes, or taxes on land, was at its height. Large gatherings of protesters in provincial areas continued throughout the epidemic, and this must surely have enabled the spread of the disease. Many preventative measures used against the spread of Cholera, strike a chord with us today during the Coronavirus pandemic. Sick victims were to be reported to the medical officer, and then removed to a hospital. Mass gatherings and funerals were banned, as authorities felt the custom of the ‘poorer classes’ to visit their sick neighbours, and attending the wake-house, would contribute to the spread of the disease. In Cork a priest was assaulted when he opposed mourners attending a wake-house. Ordinary burial rituals were abandoned, as the sheer number of dead overwhelmed churchyards and many ‘Cholera Trenches’ were opened for rapid disposal of infectious corpses. Markets and fairs were banned as the death rate soared, shops shut down, and the streets of Irish towns emptied. Enforced incarceration, and a deep mistrust of medical doctors amongst the poor, meant that any attempt at quarantine was badly received. In Tipperary town, a mob prevented a patient being removed to the hospital by medical officers. In Bundoran, the seaside visitors fled the town, with roads blocked by carriages and foot passengers, ‘all escaping from the scenes of death’. Tullamore was similarly abandoned, ‘crowds armed with pitchforks, congregated on the roads threatening anyone going to or coming from the town’. A portion of the Grand Canal was drained to block canal traffic. Ireland’s huge number of highly-visible beggars - typically women and children - were suspected of carrying the cholera from town to town. These mendicants, very mobile, were prevented from travelling, and those native to a town were ‘badged’, or registered, so that they could be clearly identified as distinct from ‘other beggars and mendicants’, who may have been harbouring cholera. Urban RefugeesBoards of Health were encouraged to set up temporary hospitals, but most were vehemently opposed. Ballyshannon mobs threatened the local landlord who dared to provide a building for a hospital. In several Irish towns, field hospitals were set up, utilising old storehouses, and even erecting tents near existing Fever Hospitals in order to cope with the swelling numbers of diseased victims. Normal town and village life in Ireland came to an end, as communities and individuals tried to isolate themselves for fear of catching the disease by physical contact. Sligo, a prosperous town of 15,000 people, was abandoned as the cholera struck. Only an estimated 4,000 people remained, with the rest escaping into the adjacent countryside, camping under hedges and in ditches, where makeshift shelters dotted the landscape. The wealthiest families paid up to £50 for accommodation in a small room in the countryside. So great was the fear of contagion amongst local country people, that few would give shelter or food to these ‘urban refugees’. A ‘cordon sanitaire’ was set up around the town, in order to prevent people from leaving. Provisions on the way to Sligo town were stopped, trenches were dug across the highways, carriers from Enniskillen was turned back, and a blockade was set up on the main road to Donegal. Prices for food and provisions increased rapidly due to lack of supply. The daily Mail Coach from Dublin appears to have got through, possibly due to its armed guards. Sligo was noted in contemporary reports as ‘strangely silent’ during the epidemic. There was complete suspension of business and an entire absence of people from the streets. ‘The only sounds heard were the footsteps of those running to seek medical aid, or the hurried footfall of the medical men, and the dreaded rumble of a cholera cart conveying the dead to the burial ground’. Commentators noted the absence of birds during the course of the contagion, probably due to the constant fumigation. Self-imposed quarantine appears to have worked in some situations, as not a single case of fever occurred at the Charter school, nor Sligo gaol, which had their own uncontaminated water supply. Sligo town recorded over 1,400 cases of Cholera, with almost 700 deaths. The mortality rate was 47.5 percent; without the flight of its people, the final toll would have been more.  Charlotte Thornley, later to be the mother of Bram Stoker, then a 14-year old girl, lived with her family in Old Market Street in Sligo. She wrote a memoir, about her experiences of the cholera, and the fact that her family survived untouched. The Thornley’s stayed quarantined in their house and fumigated it daily; they may also have had their own well, thus avoiding contaminated water. Their street was one of the few with a new sewer running through it, perhaps protecting them. Many of the Thornley’s neighbours, including a Dr. Little, died one by one, and were carried away. Charlotte has left us with a heart-rendering account of her young neighbour, Mary Sheridan, left dying alone; ‘We could hear her crying! I begged my mother’s leave to help her. She let me go with many tears. Poor Mary died in my arms an hour after and I returned home, and being well fumigated was taken in and escaped’ [the disease]. It is difficult to ascertain if isolation as practiced in Ireland during the cholera pandemic led to a reduction in death rates. What we can say, is that the number of cases and deaths were significantly lower in rural areas than in the unsanitary towns. Exceptions to this trend were in the densely settled countryside of rural west Cork, west Donegal, and west Mayo, where heavily clustered traditional clachan-type settlements, were as prone to the march of cholera as was a Dublin tenement.

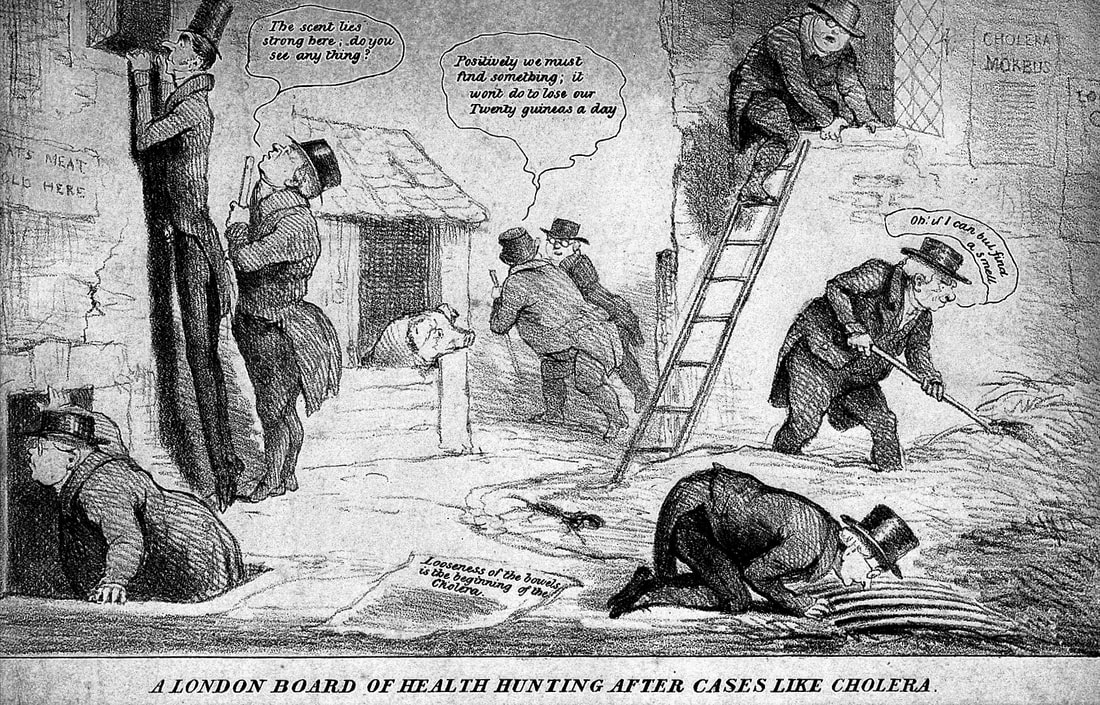

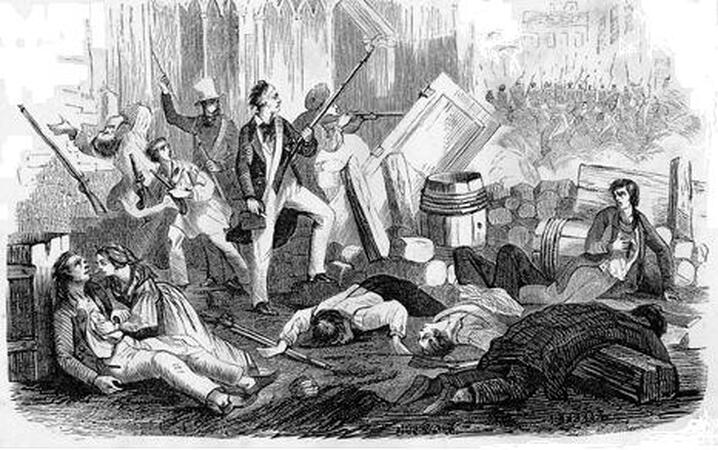

During the current Coronavirus crises, we are awash with information from all angles; from newspapers, to social media, to broadcast media, to hashtags. We are bombarded with the educated opinions of experts in the field of disease and epidemiology, who often - alarmingly to the layman – offer legitimately different opinions, giving rise to doubts. Fear, and of course fake news, leading to anxiety and irrationality, drowning out the voices of reason. But, happily we have avoided the widespread riots and violence which characterised the 1832 Cholera epidemic. Public disorder was not a feature of the recurrent outbreaks of ‘fever’ before 1832, although individuals were frequently targeted. However, the pan-European spread of Asiatic Cholera between 1830-37, ignited ‘waves of social violence’ against the rich, government officials, hospital workers, and especially doctors. The nature of this violence during the 1832 pandemic was essentially a class struggle – the poor were popularly perceived to be the reservoir of disease, and somehow complicit in outbreaks. Doctors, for their part, expressed great frustration, particularly with the poorer classes, for failing to accept modern scientific approaches to cleanliness and medicine, and the new science-based values of the period. Mistrust in the medical profession stemmed from an unfounded belief that doctors stood to ‘profit enormously’ from the fees paid to them for their services. In Sligo, a west of Ireland provincial town, public rumours speculated that doctors would be paid 10 guineas a day by the Board of Health for dealing with cases, and a further five pounds for every patient they killed. The horrific physical appearance of cholera victims, with their blue and shrivelled skin, readily gave rise to the myth that doctors were poisoning their patients, or drugging them asleep, so they could be buried alive, quickly vacating beds for new patients. The forcible removal of those with cholera symptoms, from their homes to hospitals, caused deep resentment and despair, despite its good intentions. Cholera riots were generally incited by reports that the elites and physicians, were deliberately spreading or inventing the disease to murder the poor. Many believed that the bodies of those who had died would be given over for medical dissection, then seen as a shameful and disrespectful end. Body-snatching was a real fear, and the poor felt that death in a cholera hospital would lead to the dissecting table. The banning of normal funerary and burial practices was grievous to a deeply-traditional populace. In Britain there were over 72 cholera riots recorded in 1831-32. In Ireland, the situation was compounded by the abject poverty of the great mass of people, and by the political situation of the time. Twenty-two riots are recorded throughout Ireland, including three in Sligo, two in Boyle, and outrages in towns as diverse as Derry, Drogheda, Claremorris and Kilkenny. There is little evidence to link the severity of the outbreak with actual riots – violence flared often based solely on rumour or superstition. In Ballyshannon a mob caused considerable damage to the hospital, despite the local physician working relentlessly for the poor. Interestingly, many of these mobs prominently featured women and children. One notable riot involved a future president of the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Thomas Rumley, (1792-1856). Rumley and another doctor, probably William Stoker, were requested to investigate a supposed case of Cholera in Kingstown, (Dun Laoghaire), in early 1832. Asiatic Cholera was diagnosed, but furious inhabitants rioted, - mostly boarding -house keepers of this summer resort - not wanting their town to be so blackened, and an ‘infuriated mob’ attacked the two doctors with stones and bricks; they narrowly escaped with their lives. The small towns of Ireland were more likely to experience panic and rioting that the bigger urban centres, possibly due to poorer understanding of the disease, and the easier nature of fleeing the infected areas. Rural disorder was rife by 1832, aided by the Tithe Wars. The arrival of the cholera in Sligo in August 1832 was vehemently denied, and there was ‘violent resistance’ to the Board of Health plan to fit up temporary hospitals in the town, especially one near the most densely populated part of the town. A letter of protest signed by the residents was sent to the Provost and threats made that the place would be demolished immediately the first patient was admitted. That idea was abandoned, and instead the Fever Hospital was converted to the treatment of Cholera patients. This too was met by opposition from those living nearby. A ‘ruffianly mob’ armed with clubs came in from the countryside, joined up with the poorer classes of the town and declared they ‘would have no Board of Health or Cholera Hospitals’. Similar demonstrations were organised in other country towns, significantly obstructing the exertions of those taking every precaution to prepare for the impending outbreak. There was widespread resistance to the creation of what were seen as ‘centres of pestilence’, likely to endanger the local inhabitants. As the epidemic progressed, and many medical men were seen to die in the line of duty, incidences of riots ceased, but the powerlessness and disarray of doctors in the face of such a tide of deaths, left a sense of pessimism amongst rich and poor alike.

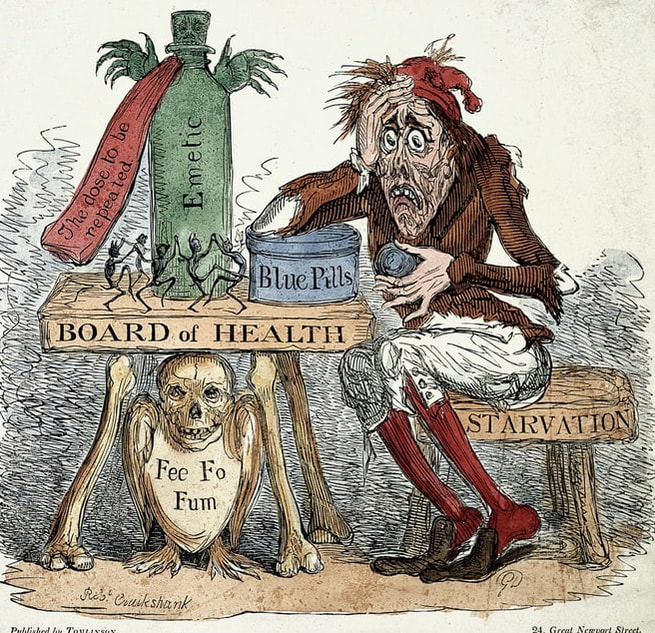

Victor Hugo’s famous novel, Les Misérables, which spawned the modern blockbuster musical, is set during the Paris Uprising of 1832, an insurrection caused in part by the outbreak of Cholera in Paris during the spring of that year, which left 18,400 of the poor dead in its wake. Dangerous 'quack' cures for the coronavirus are being shared online in the midst of the current epidemic. Lemon juice, lavender oil, elderberries, liquid silver and hot water are among the remedies being suggested on Facebook, particularly in anti-vaccination circles. This echos the raft of toxic compounds which were touted as curative during the Great Cholera Epidemic of 1832. Cholera was little understood in the early nineteenth century, and the medical profession failed to make the link between contaminated water and the disease. Miasma theory, which cited rotting organic substances as the cause of illness, held sway among public health reformers. The lack of understanding of the nature and vectors of transmission of the disease, was the main factor in its spread and epidemic character. The cholera microbe was not identified until 1883, by the physician Robert Koch, but in 1832 there was little that could be done to save an infected patient. There was, however, a vast array of purported treatments for cholera; many were based on traditional cures, and some on emerging scientific rationale. Most were simply ineffective, given the limited nature of the knowledge of the pathology of the disease. The common practice of delivering emetics and enemas to encourage purging led to a further, and often catastrophic depletion of a patient’s body fluids. Bleeding, a traditional remedy for restoring circulatory balance was a common treatment, as were the administration of mercury, opium and laudanum, common drugs during the period. The rage of substances prescribed was diverse, from ammonia, arsenic, camphor, castor-oil and even turpentine. Virtually all treatments only made the patient worse, their dehydrating effects simply hasting death. There was a belief that alcohol provided some immunity to the disease and hence it was consumed widely. Brandy and whiskey were commonly used to encourage patients to vomit, and were considered to be both preventative and curative. Whiskey mixed with ginger was frequently given to children as a daily preventative measure. Nurses at the Sligo fever hospital stayed permanently drunk in the hope of avoiding infection. Much of the populace of Sligo spent the epidemic in an intoxicated state. Who could dispense medicines? In the 1830s, Medicines were generally dispensed by Apothecaries or Chemists as we would now call them, who compounded medicines and were theoretically overseen by the College of Physicans. Physicans, (MDs), treated internal disease, and Surgeons treated external conditions, including amputations . By 1832, there was a certain amount of tension between the professions. Apothecaries could practice a limited amount of surgical tasks, and in the 1830s, there were many ‘Surgeon-apothecaries’, a prototype general practitioner, not always in agreement with the Physicians. However, all were in agreement to warn the public about trusting the 'quack' or fraudster, purveying supposed cures for the disease, and making a fast shilling off the impoverished masses. Scientific AgeToday, we are lucky to live in an age of science and with good healthcare. An outbreak of cholera today, would be quickly tackled with preventative measures such as antibiotics, rehydration and an emergency supply of clean water. But that all is dependent on a functioning civil society. Cholera is still endemic, maintained at a baseline level, always ready to erupt again. It has largely disappeared from the developed world, due to modern water treatment and efficient sewerage networks. However, it can rear its ugly head very suddenly, as was the case in Haiti, following the devastating earthquake of 2010. Continuing civil war in Yemen has lead to a debilitating and on-going cholera epidemic, and the disease is still prevalent in poorer countries in Africa and Southeast Asia. An appreciation of our own society's dalliance with cholera, should give us empathy with those who continue suffer under its lethal shadow.

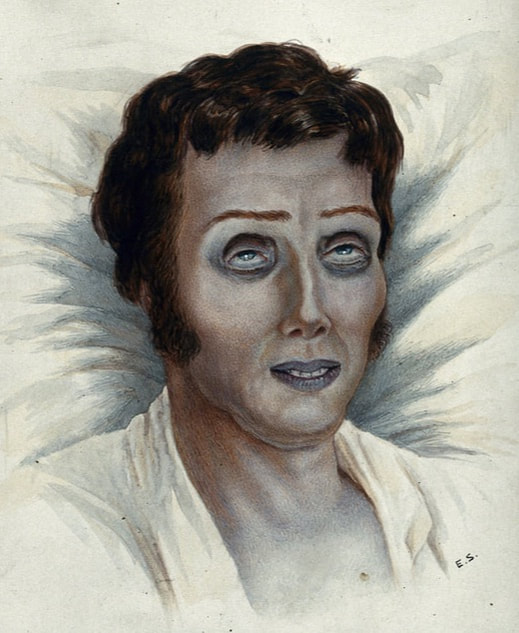

‘The contagion came from the East… gradually the terror grew on us…..we heard of it nearer and nearer….it was in Germany, it was in England, and then, - with wild affright – it was in Ireland!’ C. Thornley, 'Experiences, (1873) These words could have been written today, but in fact they reflect public fears expressed in Ireland almost 190 years ago, as the Asiatic cholera pandemic swept through Europe to these shores in 1832. Sligo claimed its place in medical history as the worst-affected town in Ireland or Britain when the epidemic hit in the sultry summer of 1832. In a six- week period the official death toll in this small provincial town, was over 700 lives; the real total was probably close to 1,000 souls. People died within hours of contracting the disease, and mass graves were opened to cope with the vast numbers of infectious corpses. Doctors battled in vain to contain the cholera, and townspeople fled to the countryside until the disease abated. All regular business was suspended in Sligo during the epidemic, a total of 24 days. The trauma of ‘The Cholera’, left an enduring mark on the folk memory of the town. The parallels with the current social and medical upheaval associated with the Coronavirus are uncannily similar, from the fear, to the cessation of normal life. What is Cholera? Cholera is a pathogen – a highly infectious bacteria, and endemic to certain parts of Asia. It has many vectors of transmission, and in 1832, the process of transmission was overwhelmingly contaminated water and the oral-faecal route. Hygiene is critical for the prevention of infection by pathogens, something that was sorely lacking in the first quarter of 19th century Ireland, particularly in urban areas. If untreated, cholera can advance within hours to cause death. It starts suddenly and quickly causes dangerous fluid loss. Symptoms of cholera infection include diarrhoea, characterized by a milky appearance known as ‘rice-water stool’. In addition, persistent painful vomiting occurs. Dehydration develops within hours after the onset of symptoms, and can be mild or severe depending on the amount of fluid lost. This can cause lethargy, sunken eyes, shrivelled skin, low blood pressure and irregular heartbeat. Cholera dehydration also causes a characteristic blue tinge to the nails and skin. The Irish descriptive name for this type of Cholera, was ‘Galar, gaimhdeach, gorm goile’, or the 'stingingly-painful, blue, stomach disease. A terrifying description for a terrifying disease. It is this dehydration that is most dangerous: it can lead to a rapid loss of minerals in the blood, which are known as electrolytes. Sudden loss of electrolytes leads to muscle cramps and shock and can lead to death in a matter of hours, even in people who were healthy beforehand.

Cholera, has often been referred to as the ‘classic disease’ of the 19th century, characterised by its epidemic outbreaks, and is frequently cited as the cause of popular agitation, and social unrest, as well as being instrumental in the drive for municipal reform and the development of public health. In modern times, cholera can be very effectively treated by re-hydration therapy, the prompt restoration of lost fluids and salts through rehydration, and by anti-biotics. The people of Sligo has no such solace in 1832. |

Dr. Fióna GallagherProfessional Historian. Main area of interest is in urban history, and the social and economic sphere of Irish provincial towns after 1700. ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed