|

Cholera: Fever, Fear and Facts A Pandemic in Irish Urban History |

|

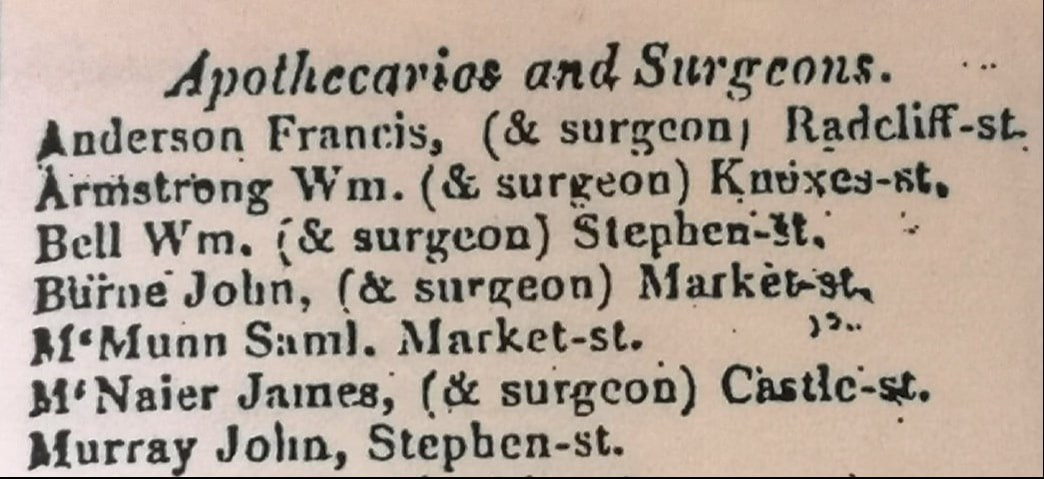

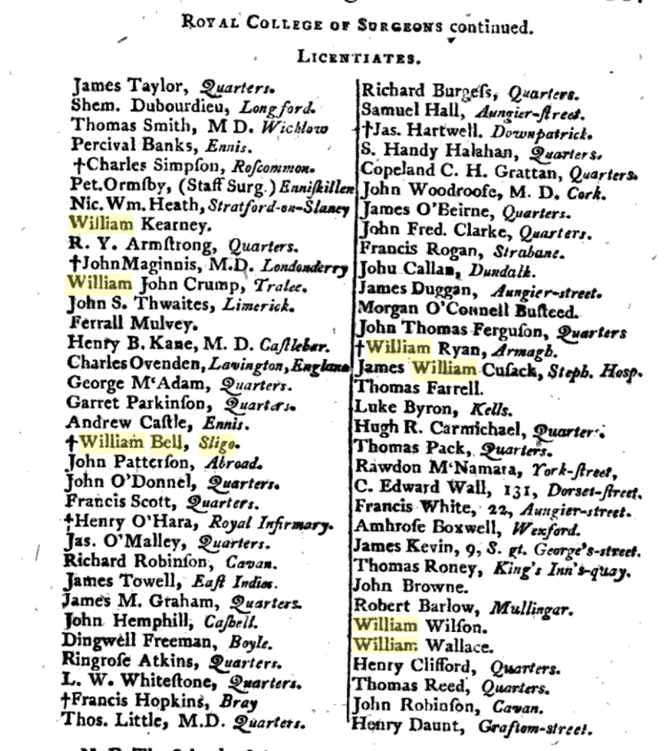

Today, Healthcare Workers are in the frontline of the Coronavirus pandemic, varying from highly-trained specialists to the non-medical ancillaries, providing the backbone for our hospitals. In the past, the delivery of care to the sick was not as sophisticated as now, but medical and logistic experience gained from Irish epidemics over the last 200 years, has been invaluable. In the pre-famine period, physicians, surgeons, apothecaries, midwives and medical officers operated across a wide-array of private practice, charitable & fever hospitals, dispensaries poor-houses, and home visitations. During the 1832 Cholera epidemic, the rudimentary Irish medical system was challenged in several ways, not least in the exposure of doctors, nurses and attendants to the disease. While death-rates amongst the poor were greater, cholera struck down the better-off as well. Among the higher classes, doctors, apothecaries and clergymen were particularly at risk, for their duties brought them into close contact with the sick. A great obstacle to setting up cholera hospitals was the difficulty in hiring staff to look after the infected patients. Nursing was not a recognised profession in the 1830s; a Matron’s role at hospitals was primarily an administrative one. Nursing attendants, or ‘nurse-tenders’, often male as well as female, were confined to washing and feeding patients and cleaning the wards, and were poorly educated and paid. A higher standard of nursing care, came from religious sisters, most notably the new congregations of un-cloistered nuns, who, fulfilling their vows of charity, visited the sick poor in their homes from about 1820. During the Cholera epidemic both the Mercy Sisters and Sisters of Charity served at Grangegorman and Townsend Street in Dublin, for several months, where their strict religious discipline and attention to cleanliness, yielded good outcomes, and was much-commented on by the medical men. The success of their endeavours led to three Sisters leaving for Paris in 1833, for specialist nursing-study. In 1835 Mary Aikenhead founded St Vincent’s, a free hospital wholly-owned and operated by religious women who were also qualified nurses, in a profession then utterly dominated by men. In Dublin, competent lay nurse-tenderers worked in Grangegorman and the mendicity institutes, and several hundred of these served diligently in the capital, even helping to bury the dead. The professionalisation of nursing as a secular job was not to happen until Florence Nightingale's establishment of St. Thomas's in 1860. The practice of medicine however, was a largely a profession for the sons of the gentry and the upper-middle classes; a ‘respectable class of society’. The profession was characterised by a tripartite division of physicians, surgeons and apothecaries, who looked upon each other as ‘practitioners of totally different trades’, rather than colleagues. One thing however, united them all; a high level of mortality. As Geary succinctly puts it, ‘Medicine was a dangerous occupation in pre-Famine Ireland’. An 1843 survey undertaken by renowned doctors Stokes and Cusack, concluded, that ‘in Ireland a medical officer runs a greater risk of death from contagious disease than perhaps any other country in Europe’. Irish doctors were more exposed to diseases than the middle-class was generally, and over a long period of their professional lives. A significant proportion of doctors in the pre-famine period contracted Typhus, then endemic amongst the destitute poor. Medicine was a hierarchy, with clear lines of demarcation. Physicians were considered the senior ‘learned’ profession, recipients of a university education, with an extensive knowledge both medical and philosophical. Surgeons, licentiates of a professional body, (the RCSI), were regarded as skilled craftsmen, served a robust apprenticeship studying anatomy, surgery and pharmacy, but were regarded as ‘professionally inferior’ to physicians. In fact many surgeons of the time in Irish hospitals were battle-hardened, having served in the army during the Peninsular wars, where they acquired remarkable experience which allowed them to administer innovative treatments when they returned home. Licensed Apothecaries, (akin to modern pharmacists), compounded their own medicines, and gave minor medical advice. Many surgeons were also apothecaries. There was a certain tension between the Apothecaries and Physicians over the compounding and sale of medications, and what the Physicians viewed as apothecaries' unlawful ‘practice of medicine’. However, the services of apothecaries were affordable to the poor, and they considered themselves the historic providers of medicine to the people. Overall, there were great discrepancies in the professional characters of Irish doctors during this period, ranging from total dedication, to the total dereliction of duty, the latter prevalent amongst country doctors. One obituary mentions a nurse, Mrs. Margaret Glancy, of the Antrim cholera hospital, who died on 16 September, having caught the disease while attending a fatal case some days previously. Cholera took a huge toll on medical men around the country, as can be seen through the columns of provincial papers. Between May 1832 and April 1833, around 75 medical men are recorded as dying from Cholera. There were probably many more. The highest toll was on Surgeons, perhaps due to their positions in local Fever Hospitals; Thirty died. Twenty-four Physicians and eighteen Apothecaries also lost their lives. Epitomising the tragedy behind the facts, is Surgeon Alexander McKee, of Moneymore, Derry, aged 45, a garrison surgeon and widower, who died in January 1832, ‘after 22 days of great suffering’, contracted from the poor he was attending at the Drapers Dispensary. He left six infant children without a mother, to deplore his irreparable loss’. In Galway, dispensary apothecary Matt Doyle, succumbed to the fever in May, as did Surgeon Richard Jebb Browne, of Newry, aged 58, one of several military surgeons to die. In Carlow, the assistant Surgeon John Foster and his wife died in early June, one of nine cases in the town, including another physician. The young Dr Connell Evans, a country practitioner from Rathkeale, came to help in Barrington’s Hospital, Limerick, but died 24 hours after coming into contact with his patients. Doctor Cox, late of Portarlington, died at Newbridge on 16th June, collapsing and dying in two hours; an apothecary in attendance at Ennis Cholera hospital, Mr. Carr, died of the disorder on 9th June, followed by his wife less than 24 hours later. Dr Charles Keane, newly married, died on 16th August, ‘a victim to his own benevolence and humanity’; he contracted the disease during his attendance at Limerick and Ennis cholera hospitals. His remains were conveyed from Ennis to the family vault at Kilmaley, west of the town, accompanied by a vast congregation of country people, in defiance of the ban on funerals. Sligo Doctors during the EpidemicSligo was to experience a concentrated and tragic loss of its doctors during the Cholera epidemic. Seven doctors died within eight weeks, including some who had been sent to Sligo by the Central Cholera Board to assist local physicians. In 1832 there were about ten doctors practicing in the town, along with a number of apothecaries. Dr Henry Irwin (c.1770-1836), a former army surgeon, was chief physician at Sligo Fever Hospital when the epidemic hit. He left behind a vivid account affair in the town, and the difficulties faced by doctors and the Board of Health. Doctors Leahy, Bernard Coyne and the Fever-Hospital Surgeon William Bell all died of the pestilence. Surgeon Bell, a licentiate of the RCSI, was buried in the Cholera Pit to the rear of Sligo Fever hospital, along with his patients. Dr Leahy was Professor of Physics at the ‘Kings and Queens College, (RCPI), and had been sent to Sligo by the Central Board of Health, so bad was the situation there. Several private practitioners residing in Sligo also died, including Dr Anderson and his daughter; Drs Beatty, Church and Sherlock, while Drs Devitt and Carter were severely afflicted but recovered. Five other resident doctors attached to the hospital, Doctors Knott and Powell, Murray, Carter, and Tucker, fell ill with the cholera, but survived. A medical student, William Christian, died in May 1833, having survived an attack of cholera the previous September, when he was lauded for his ‘unceasing exertions and benevolent care to the poor’. Many of the auxiliary ‘nurse-tenders’ at Sligo Fever Hospital died or fled in fear. Dr. Irwin, noted that the only replacements that could be employed in place of the regular staff, were the ‘most abandoned of both sexes, several of whom, from their drunkenness and inattention, we were obliged almost immediately to dismiss.’

In our current situation, we can be very glad of our modern medical professionals and their services; they draw on a long line of medical tradition in Ireland.

1 Comment

|

Dr. Fióna GallagherProfessional Historian. Main area of interest is in urban history, and the social and economic sphere of Irish provincial towns after 1700. ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed